Yesterday, which proved an unseasonal bright, warm, day, I biked (with a new wheel!) to the east of Paris—in the Gare de Lyon district where I lived for three years in the 1980’s—to attend a Mokaplan seminar at INRIA Paris, where Anna Korba (CREST, to which I am also affiliated) talked about sampling through optimization of discrepancies.

Yesterday, which proved an unseasonal bright, warm, day, I biked (with a new wheel!) to the east of Paris—in the Gare de Lyon district where I lived for three years in the 1980’s—to attend a Mokaplan seminar at INRIA Paris, where Anna Korba (CREST, to which I am also affiliated) talked about sampling through optimization of discrepancies.

This proved a most formative hour as I had not seen this perspective earlier (or possibly had forgotten about it). Except through some of the talks at the Flatiron Institute on Transport, Diffusions, and Sampling last year. Incl. Marilou Gabrié’s and Arnaud Doucet’s.

This proved a most formative hour as I had not seen this perspective earlier (or possibly had forgotten about it). Except through some of the talks at the Flatiron Institute on Transport, Diffusions, and Sampling last year. Incl. Marilou Gabrié’s and Arnaud Doucet’s.

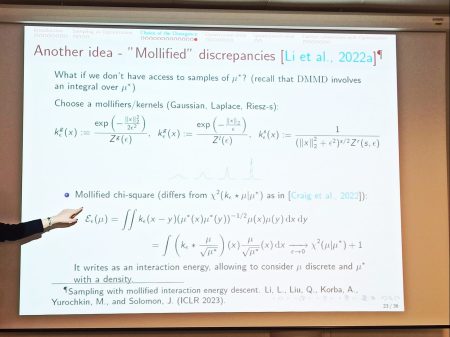

The concept behind remains attractive to me, at least conceptually, since it consists in approximating the target distribution, known up to a constant (a setting I have always felt standard simulation techniques was not exploiting to the maximum) or through a sample (a setting less convincing since the sample from the target is already there), via a sequence of (particle approximated) distributions when using the discrepancy between the current distribution and the target or gradient thereof to move the particles. (With no randomness in the Kernel Stein Discrepancy Descent algorithm.)

The concept behind remains attractive to me, at least conceptually, since it consists in approximating the target distribution, known up to a constant (a setting I have always felt standard simulation techniques was not exploiting to the maximum) or through a sample (a setting less convincing since the sample from the target is already there), via a sequence of (particle approximated) distributions when using the discrepancy between the current distribution and the target or gradient thereof to move the particles. (With no randomness in the Kernel Stein Discrepancy Descent algorithm.)

Ana Korba spoke about practically running the algorithm, as well as about convexity properties and some convergence results (with mixed performances for the Stein kernel, as opposed to SVGD). I remain definitely curious about the method like the (ergodic) distribution of the endpoints, the actual gain against an MCMC sample when accounting for computing time, the improvement above the empirical distribution when using a sample from π and its ecdf as the substitute for π, and the meaning of an error estimation in this context.

Ana Korba spoke about practically running the algorithm, as well as about convexity properties and some convergence results (with mixed performances for the Stein kernel, as opposed to SVGD). I remain definitely curious about the method like the (ergodic) distribution of the endpoints, the actual gain against an MCMC sample when accounting for computing time, the improvement above the empirical distribution when using a sample from π and its ecdf as the substitute for π, and the meaning of an error estimation in this context.

“exponential convergence (of the KL) for the SVGD gradient flow does not hold whenever π has exponential tails and the derivatives of ∇ log π and k grow at most at a polynomial rate”

lass and a central administration. Which the central characters in the

lass and a central administration. Which the central characters in the