In a “Feature” article of 21 January 2021, Nature goes over a poll on “software tools that have had a big impact on the world of science”. Among those,

In a “Feature” article of 21 January 2021, Nature goes over a poll on “software tools that have had a big impact on the world of science”. Among those,

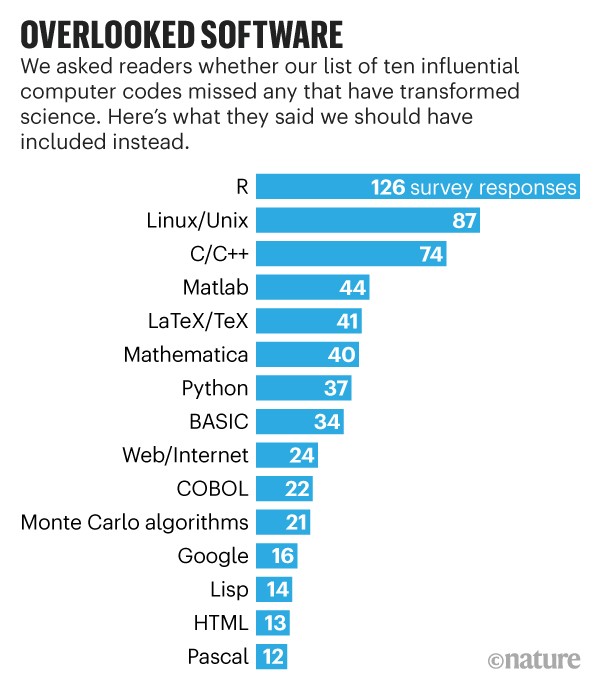

the Fortran compiler (1957), which is one of the first symbolic languages, developed by IBM. This is the first computer language I learned (in 1982) and one of the two (with SAS) I ever coded on punch cards for the massive computers of INSEE. I quickly and enthusiastically switched to Pascal (and the Apple IIe) the year after and despite an attempt at moving to C, I alas kept the Pascal programming style in my subsequent C codes (until I gave up in the early 2000’s!). Moving to R full time, even though I had been using Splus since a Unix version was produced. Interestingly, a later survey of Nature readers put R at the top of the list of what should have been included!, incidentally including Monte Carlo algorithms into the list (and I did not vote in that poll!),

the fast Fourier transform (1965), co-introduced by John Tukey, but which I never ever used (or at least knowingly!),

arXiv (1991), which was started as an emailed preprint list by Paul Ginsparg at Los Alamos, getting the current name by 1998, and where I only started publishing (or arXiving) in 2007, perhaps because it then sounded difficult to submit a preprint there, perhaps because having a worldwide preprint server sounded more like bother (esp. since we had then to publish our preprints on the local servers) than revolution, perhaps because of a vague worry of being overtaken by others… Anyway, I now see arXiv as the primary outlet for publishing papers, with the possible added features of arXiv-backed journals and Peer Community validations,

the IPython Notebook (2011), by Fernando Pérez, which started by 259 lines of Python code, and turned into Jupyter in 2014. I know nothing about this, but I can relate to the relevance of the project when thinking about Rmarkdown, which I find more and more to be a great way to work on collaborative projects and to teach. And for producing reproducible research. (I do remember writing once a paper in Sweave, but not which one…!)

“Prebuilt into macOS and Unix systems (…) the command line (also called the shell) is a powerful text-based interface in which users issue terse instructions to create, find, sort and manipulate files, all without using the mouse. There are actually several distinct (…) shell systems, among the most popular of which [sic?] is Bash, an acronym for the ‘Bourne again shell’ (a reference to the Bourne shell, which it replaced in 1989).”

“Prebuilt into macOS and Unix systems (…) the command line (also called the shell) is a powerful text-based interface in which users issue terse instructions to create, find, sort and manipulate files, all without using the mouse. There are actually several distinct (…) shell systems, among the most popular of which [sic?] is Bash, an acronym for the ‘Bourne again shell’ (a reference to the Bourne shell, which it replaced in 1989).”